There’s a moment, in the first half of Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, upon which the final film in the Skywalker saga hinges. Regardless of your feelings by the end of the film, I think we can all agree that this no-turning-back point, which seems to set the tone for Rey’s journey of self-discovery as a Jedi, is unanimously devastating. Even in a series known for lopping off limbs and amassing a minimum of one major character death per film, this plot beat is a game changer.

And then, in the very next scene, J.J. Abrams immediately reverses it.

[Spoilers for Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker.]

I’m talking, of course, about the “death” of Chewbacca.

When Rey explodes the First Order’s transport ship with accidental Force lightning on Pasaana, it is catastrophic. Her Force tug-of-war with Kylo Ren has unexpectedly escalated to Palpatine-level powers, at the expense of a dear friend’s life. Suddenly she’s been thrust from the comfort of the past year of Jedi training to the bleak reality of battle; there is collateral damage far beyond cracked earth or broken trees.

In the moment, even as I shrieked along with the rest of our theater, I wondered if this were a nod to the Legends canon, specifically R.A. Salvatore’s novel Vector Prime. In 1999, the book kicked off the New Jedi Order series with the, frankly, traumatic choice to kill off Chewie. And not just with an exploded ship, but by dropping an entire moon on him. It was the Star Wars Expanded Universe equivalent to Dumbledore dying, the message we’re not messing around loud and clear.

That final image, of Chewbacca raging against the light on the dying planet of Sernpidal, is also what fractures the Legends version of the Solo family. Sitting in the theater, it didn’t seem like such a stretch for Abrams to have sacrificed Chewie for a similar aim, to shove Rey toward the dark side she’d been so desperately ignoring. Instead, before there’s any opportunity to parse how Rey’s actions might have created a rift between her and her friends, the audience learns in the very next scene that our beloved Wookiee is alive and well, if still imprisoned.

Buy the Book

Network Effect

Abrams could have utilized this dramatic irony of the audience knowing vital information that our heroes don’t, playing the tension of Rey panicking that she is becoming the Sith killer of her nightmare visions, or of her friends fearing her growing powers. But once they reach Kijimi, Rey can suddenly sense that Chewie is alive—and there are no consequences for what could have been a life-ruining mistake. Our heroes have snapped back to the status quo so abruptly that the Chewie scenes may as well have never happened.

This emotional whiplash in the space of just a few minutes is what makes The Rise of Skywalker such a poorly plotted film. No doubt that Abrams was working with too many moving parts, between wrapping up three trilogies’ loose ends, undoing some of Rian Johnson’s work from The Last Jedi, and working with what footage existed of Carrie Fisher; and that this dictated the final structure of the movie. There simply wasn’t enough breathing room to insert more scenes between the beats of Rey believing she did the unthinkable and Rey being absolved.

But then why attempt this character development in the first place if they were not willing to do it properly?

Let me be clear: I did not want Chewie to die. I want that poor Wookiee to live a good long life and someday properly retire on Kashyyyk with his long-suffering family from the Star Wars Holiday Special. But at the same time, I expected a final film of a final trilogy to commit more to points of no return.

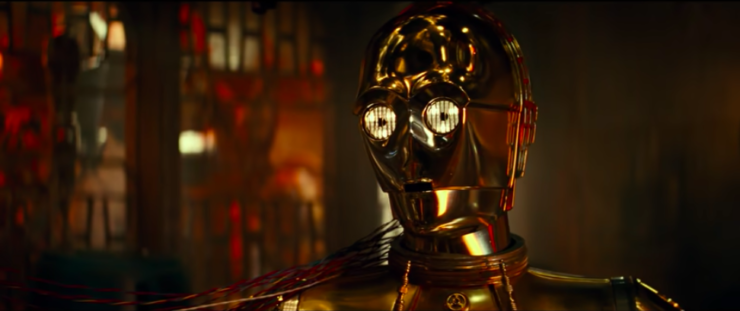

To wit: Threepio’s memory wipe. Even though the protocol droid has gotten his memory wiped at least twice in the series, this time feels more fraught—because for once, it is his choice, and because there is no guarantee that he’ll be able to restore those files. For a figure so often the butt of jokes, in The Rise of Skywalker Threepio gets two gut-punch moments: when he takes a final look at his friends to remember them; and later, during the final battle prep, his first interaction with Artoo as if they have never met before.

The astromech droid’s distressed beeps tell you all you need to know about how awful this moment of nonrecognition is… yet it’s a mere blip in the larger frenzy of bombing Star Destroyers and fighting Palpatine. The instant that there is a break in the action, Artoo produces the backups of Threepio’s memory, restoring his friend to near-perfect condition before the audience has had time to properly mourn his loss.

Perhaps we shouldn’t have been surprised—Finn mentions Artoo’s backups even before Babu Frik clears Threepio’s cache. But why introduce a potential fix (even if Threepio pessimistically dismisses it) and then supply exactly that solution at the end? This and Chewbacca’s miraculous survival are unnecessary emotional detours in an already overstuffed story, not worth the energy of engaging because it won’t mean anything in the end. If you bring back your good guys, you’re not telling us anything we don’t already know.

Maybe this was actually Abrams’ intention. After all, this is a movie whose opening crawl proclaims The dead speak! If not even Palpatine can stay dead, how can we expect any of our heroes to be lost? Yet to waste your audience’s emotional energy on these reversals, to push them toward distrusting any and all emotional beats instead of taking that time to shade in side characters more, is bad storytelling. In an alternate universe, there’s a version of The Rise of Skywalker where Chewie’s death alienates Rey from her friends, or Threepio’s memory is just another casualty of war, and it is a better movie.

And it’s a shame that Abrams relies so much on hollow plot reversals, because the one time in The Rise of Skywalker where he uses this device effectively is actually excellent: Rey and Kylo Ren/Ben Solo’s Force dyad bond, represented in their back-and-forth exchange of life force.

Rey is not the first Jedi to be tempted toward the dark side, nor is Kylo Ren the first villain to ponder returning to the light. But they both vacillate on that spectrum more than any of their forebears—Luke, Vader, Anakin—over the course of this trilogy, and especially in relation to one another.

When Rey impales Kylo on his own lightsaber, right as Leia has used up the last of her own energy to reach across the galaxy for her son Ben, it’s the Chewie situation all over again: Caught up in the rage of battle, in the frustration of others (especially him) claiming to know who she is, Rey lashes out with the same dark power that sparked Force lightning—and instead of an exploded ship, it’s her archenemy slumped at her feet with a fatal stab wound. But where Chewie was saved by sheer luck, here Rey deliberately decides to reverse what should be an awful no-going-back moment, healing Kylo with some of her own life force before he’s even properly died.

Twice now, Rey has teetered on the brink of darkness, then caught herself at the edge. Anakin Skywalker didn’t have that option when he helped Palpatine throw Mace Windu out the window of his office, nor when he Force-choked a pregnant Padmé and finally drove her away. He made these rash, irreversible decisions and had no choice but to lean into them, embracing the dark side and the Sith. Ironically, what started him on that path was a vision of Padmé dying and his desperation to learn how to cheat death—something that, at least according to a young Palpatine, could not be learned from the Jedi. Yet Rey’s harnessing of life force came from the sacred Jedi texts themselves; and each time she utilizes that power, she chooses the light side over and over.

Rey resurrecting her nemesis right after striking him down could have been as whiplashy as the Chewie reversal, if it had had no bearing on the rest of the plot. But unlike the latter, Rey learns something from this encounter. It’s not that she brings back Kylo Ren—she sees, in the moment she runs him through with his own blade, that she has killed Ben Solo, or at least the potential of him. So she gives him back his life, and the opportunity to reject his Knight of Ren and Supreme Leader persona—with the help of memory!Han—by throwing away his saber.

Even there, the reversal almost doesn’t succeed. Because in addition to tossing aside his saber, Ben has also lost the scar that Rey gave him in The Force Awakens; her healing erased that wound from their first major confrontation. Such an act seems to echo the earlier reversals’ issue of bouncing back to an earlier time without consequences. However, Abrams et al were clearly trying to make a point of reverting Kylo Ren back to Ben Solo on every level imaginable, from dress to expression.

And it’s not what he looks like that matters in the final battle against Palpatine, but what he does: fighting alongside Rey, figuratively if not literally. He defeats the Knights of Ren while she, inspired by the voices of the Force and armed with twin Skywalker sabers, turns Palpatine’s dark side lightning back on him—and dies in the process. And he fulfills his final purpose in healing her back.

In keeping with Ben’s redemption arc, it’s the right thing to do—returning the favor. Narratively, however, it is the film’s first and only reversal with conditions. The life force that Ben transfers back to Rey is the same amount that she had given him—no more, no less. It’s the first law of thermodynamics (energy is neither created nor destroyed, only transferred or changed from one form to another), filtered through the dyad in the Force.

Did Rey know that the situation might arise in which she would need to reclaim that gifted life force? Did Ben know he was living on borrowed time? It’s the rare case in which The Rise of Skywalker’s ambiguity is appreciated. Regardless, it introduces constraints and consequences; the story doesn’t just rubber-band back as if nothing happened. A villain’s resurrection becomes a hero’s death; Ben Solo gets his redemption; and nobody-turned-Jedi Rey Skywalker proves that, as she always has, she deserves to live.

Natalie Zutter wishes her experience of watching The Rise of Skywalker hadn’t been quite so skeptical, but she hopes that a second watch will smooth it out a bit. Share Star Wars memes with her on Twitter!